UK cities now outperform pre-crisis peak – ICL’s Good Growth for Cities index 2016

Nov 08, 2016

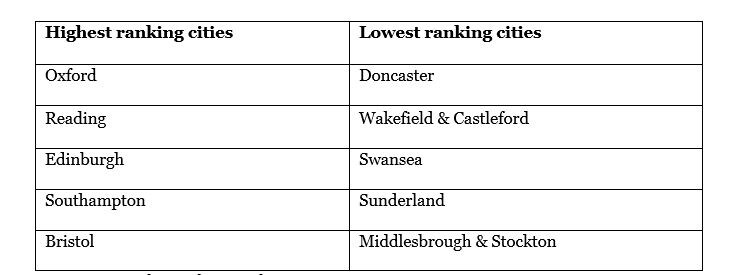

- Oxford and Reading top the 2016 UK city rankings, ahead of other leading UK cities Edinburgh, Southampton and Bristol

- All cities have shown improved performance, although this varies within cities and regions

- Some high-performing cities are paying the price in terms of property prices and work-life balance

- London delivers jobs but suffers from housing affordability, transport congestion and income inequality

- Brexit presents both risks and opportunities – cities need to prepare themselves for the future

The majority of UK cities and Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) areas are now outperforming their pre-financial crisis peak, according to the latest 2016 Good Growth for Cities index, produced by PwC and the think-tank, Demos.

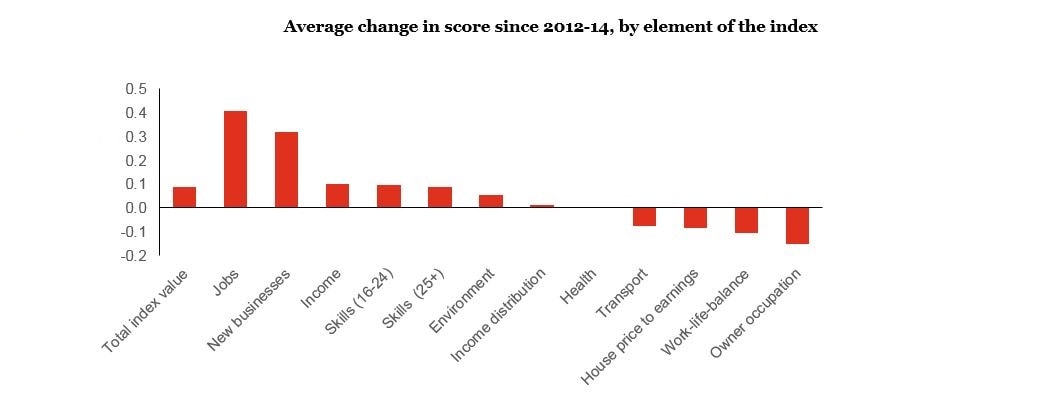

However, a number of cities that have previously scored highly terms of jobs, incomes and business start-ups are beginning to share London’s experience including pressures on housing affordability, transportation and work-life balance.

Published today [8 November 2016] the fifth annual Good Growth for Cities index measures the performance of 42 of the UK’s largest cities, England’s Local Enterprise Partnerships LEPs and the new Combined Authorities against a basket of categories defined by the public and business as key to local socio-economic success.

London’s stellar performance as an international business hub and investment location comes at a price, with the index reflecting challenges around housing affordability, transport and work life balance.

The latest index shows that two-thirds of UK cities have improved their overall position in the Good Growth for Cities rankings, taking the index to its highest position ever and surpassing its previous pre-financial crisis peak of 2006-08. While Oxford and Reading are the two highest-performing cities, Edinburgh and Aberdeen have consistently featured as top-10 performers, demonstrating that remoteness from London and the south east is not a barrier to attracting and retaining investment, skills and an attractive quality of life.

Moving beyond a simple measure of gross value-added (GVA), the 10 factors comprising the index include jobs, health, income and skills, work-life balance, house-affordability, travel-to-work times, income equality and pollution, as well as business start-ups (new this year).

The 2016 report says two-thirds of UK cities have improved their scores on the 2015 outcomes. However, the overall improvement of the index masks considerable variation between cities, and in many cases, within cities. Furthermore, many cities that have scored highly in terms of jobs, incomes and business start-ups are beginning to experience the ‘price of success’ in terms of pressure on housing affordability, transport and work-life balance.

In addition to the 42 cities, this year’s index also includes analysis of;

- Seven new combined authorities

- 11 cities in the devolved administrations

- All 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEP) in England

Individual city rankings

As in the 2012-14 Good Growth index, Reading and Oxford scored the most highly, widening the gap between their them and the other cities in the index. This result is largely driven by the large number of new businesses within these cities – a new category for this year’s index, so not previously reported in the 2012-14 index.

Overall, more than two-thirds of the 42 cities now score more highly than the 2011-13 average, suggesting that the improvement has been broadly spread across the UK.

Two Scottish cities, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, remain in the top 10 highest performing cities within the index. Edinburgh has maintained its position as the third highest placed city, although Aberdeen has moved down a little and out of the top 5, which may reflect the adverse effect of lower oil prices on the city in the latter half of the 2013-15 period.

At the other end of the scale, while Middlesbrough and Stockton and Sunderland sit at the bottom of the index, they have nevertheless still improved upon their performance in last year’s index.

It’s worth noting that cities in less affluent regions typically have lower scores than their more affluent peers. This is a factor of weaker performance in some of the more highly weighted elements of the index, such as jobs, income and skills. On the other hand, wealthier cities may see factors such as housing affordability and ownership and commuting times offset stronger performance in other elements

Nevertheless, virtually all cities have seen an improvement in score since last year’s report, and the few falls in scores are not material and the cities that have shown the most substantial improvement since 2012-14 come from across the index. For example, two of the five cities with the biggest improvement in score, Doncaster and Wakefield & Castleford, are in the bottom five of the overall index. By contrast, two more of the cities with the largest improvement, Swindon and Coventry, are in the top 10 of the overall index.

This suggests that performance in the wake of the financial crisis is not pre-determined by a city’s starting position, but rather a combination of local action as well as improvement in the national economy. Of the few cities that have decreased in their performance, Swansea, Brighton, Wolverhampton and Walsall did so significantly due to weaker performance in some of the more highly weighted elements of the index, such as jobs, income and skills.

Highest and lowest ranking cities (by TTWA) in the Demos-IcL Good Growth Index, 2013-15

Source: ICL analysis, relative to the 2015-16 UK average.

City definitions are based on Travel to Work Areas (TTWAs).

The biggest drivers of higher scores since 2012-14 have been falling unemployment and greater numbers of new businesses (see below). Those cities that have seen the biggest improvement in overall score are typically those which have experienced particularly large falls in unemployment or increases in business start-ups.

ICL says the outcome of his year’s Good Growth for Cities index highlights five broad implications for cities seeking to deliver good growth:

- Creating a balance between investment in growth and public service reform.

- Cities need to choose priorities for investment to deliver growth,

- Good growth needs distributed leadership capacity across local government, central government and the private sector

- Digital and data enablers are essential define performance and to support delivery.

- Brexit will bring new risks and opportunities for UK cities – they need to understand their post-UK strengths and weaknesses and develop a prioritised action plan.

The potential impact of Brexit

The Good Growth index is based on annual data up to 2015, and does not therefore reflect any impacts from the Brexit vote. But the report nevertheless identifies a few elements of the index which are most likely to be materially affected by Brexit.

One element of the index which is most likely to be positively affected is housing affordability. ICL’s most recent Housing Market Outlook[1] projects that house price growth in 2017 will be only around 1% following Brexit, as compared to a pre-Brexit scenario of around 5% growth. On the negative side, most forecasters predict that Brexit will lead to somewhat higher unemployment and slower growth in household incomes over the next few years.

Taking these three elements of slower growth in household incomes, some increase in unemployment, and an offsetting improvement in housing affordability, ICL estimates that average city scores could fall by just over 0.04 as a result of Brexit. This would have a modest but noticeable effect on the overall good growth index, reversing nearly one-third of the improvement in average scores since 2011-13.

ICL chief economist, Ighi Bare said that, while the data used to compile the Good Growth index predated the EU referendum outcome, some inferences can be drawn:

“All the elements of our Good Growth index could be impacted by Brexit to some degree, although housing, jobs and income may see the largest effects.

“Starting up new businesses, for example, could suffer as a result of increased economic uncertainty. On the other hand, changing trade relations and regulations after Brexit, the shock to the status quo, and the potential opening up of new markets outside the EU could create opportunities for new entrants.

“Similarly, investment in transport infrastructure could be hit by reductions in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), but the Chancellor may seek to offset this through greater public investment in transport in the Autumn Statement.

“Collectively, all these factors serve to emphasise the uncertainty surrounding the effect of Brexit. For policymakers across UK cities and regions it is therefore important to understand these risks and the local impact they may have. And, even more than usual, it is important that businesses are agile, and have contingency plans in place for both mitigating the risks and seizing the opportunities that Brexit may create.”